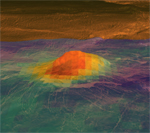

This month in Science Roundup:  Science, Language, and Literacy Science, Language, and LiteracySpecial Online Collection Science is about generating and interpreting data, but it is also about communicating facts, ideas, and hypotheses. For students unfamiliar with the language or style of science, the deceptively simple act of communication can be a barrier to understanding or becoming involved with the science. In a special section of the 23 Apr 2010 Science, Review and Perspective articles addressed various aspects of achieving science literacy, from the challenges of understanding academic language to the value of argumentation skills in learning science. A related Editorial highlighted the benefits of forging a connection between literacy and science teaching; an Education Forum discussed how literacy skills have evolved and can be compared internationally, and a Report examined how both genetics and the teachers available affect a child's literacy skills. In its 20 and 27 April issues, Science Signaling presented a set of Teaching Resources illustrating signal transduction pathways as well as student-authored Journal Clubs on topics ranging from signaling in cells of the immune system to signaling in plants. And a Science Careers article explained how faculty who teach science to nonmajors promote science literacy overall. Cooperation and Punishment In group endeavors, there is often a tension between working for the greater good of the group and working for one's own benefit. Two Reports in the 30 Apr 2010 Science -- one theoretical and one experimental -- examined the roles of cooperation and punishment in such endeavors (see the related Perspective by L. Putterman). Janssen et al. designed a game in which participants had to work together to manage the resources of an experimental environment, such as a forest or a fishery. The researchrs found that communication among the group members was key, both for establishing a maintainable rate of harvesting as well as enforcement via punishment of non-compliers. Moreover, punishment was actually found to be counterproductive when not coordinated by the group as a whole, or when it did not have the approval of group members. Boyd et al. presented a theoretical model of coordinated punishment among ancestral human populations showing that punishment, which is a costly activity, is most effectively levied when implemented with the approval of group members. In other words, coordinated punishment works to the benefit of the group, whereas individual actions do not.  Australopithecus sediba Australopithecus sedibaOur genus Homo is thought to have evolved a little more than 2 million years ago from the earlier hominid Australopithecus -- but there are few fossils that provide detailed information about this transition. Now, in a Research Article in the 9 Apr 2010 Science, Berger et al. describe two partial skeletons, including most of the skull, pelvis, and ankle, of a new species of australopith: Australopithecus sediba. The fossils -- which represent a boy, perhaps 11 or 12 years old, and an adult female -- were found in Malapa cave in South Africa and date to about 1.8 to 1.9 million years ago (a related Research Article by Dirks et al. detailed the age and geological setting of the finds). The fossils show a combination of features typical of australopithecines -- including a relatively small brain and body size and very long arms -- but also share more advanced characteristics with the earliest Homo species including smaller teeth, certain facial features, and aspects of the pelvic structure (see the related News story by M. Balter). In a related podcast interview, Lee Berger explains that the particular mix of primitive and derived features seen in the skeletons makes A. sediba unique. The team further contends that the new species shares more advanced features with early Homo than any other australopith species and may thus shed light on the evolution of that genus. Superinfection Mechanism Cytomegalovirus (CMV), a type of herpes virus, infects a large percentage of the world's population. Most of those infected develop no ill effects, but CMV infection can cause serious symptoms in immunocompromised individuals and newborns. CMV is unusual in that it can re-infect hosts who are already infected with the virus, even in the presence of a strong, specific immune response. In a Report in the 2 Apr 2010 Science, Hansen et al. found that CMV establishes these superinfections by evading the part of the immune response mediated by CD8+ T cells. The team found that superinfection requires the expression of virally encoded proteins that inhibit the process by which foreign antigens are presented to these cytotoxic T cells. They showed that in rhesus macaques, CMV mutants lacking the genes for these inhibitory proteins were able to establish an initial infection, but not to superinfect. The team further showed that depletion of CD8+ T cells (which would normally destroy virally infected cells) from the monkeys allowed subsequent infection by the mutant viruses. The results highlight the difficulties in developing an effective protective vaccine against CMV itself, but suggest that CMV-based vectors may be useful in other vaccine efforts such as those against HIV. A Perspective by H. Hengel and U. H. Koszinowski highlighted the study. Asian Monsoon Atlas The Asian monsoon system affects more than half of humanity worldwide, yet the dynamic processes that contribute to its variability are not well understood. In a Report in the 23 Apr 2010 Science, Cook et al. add substantially to our knowledge of past monsoon behavior with a Monsoon Asia Drought Atlas (MADA) -- a 700-year record of monsoon variability based on tree-ring data from more than 300 sites across Asia. The new data confirm that drought and wetness in the monsoon region are spatially heterogeneous, even though the region is under the influence of one large-scale circulation pattern commonly referred to as the monsoon. An accompanying Perspective by E.R Wahl and C. Morrill explains that this finding is particularly important for predicting hydrological changes in the region. In addition, the record reveals the spatiotemporal details of known historic monsoon failures and reveals the occurrence, severity, and fingerprint of previously unknown monsoon megadroughts and their relation to large-scale patterns of tropical Pacific sea surface temperatures. In a podcast interview, lead author Ed Cook discussed further details about the work and its applicability to current and future climate models.  Volcanism on Venus Volcanism on VenusThe surface of Venus shows clear signs of past volcanism, but are there active volcanoes on Venus today? Knowing the answer to this question would have important implications for understanding the planet's interior dynamics as well as the evolution of its climate. In a Report in the 30 Apr 2010 Science (published online 8 Apr), Smrekar et al. investigated venusian volcanism by looking at lava flows from three previously identified hotspots, which together with six others, are believed to overlie mantle plumes analogous to the hotspots of Hawaii and Iceland, and to be the most likely sites for current volcanic activity on Venus. Observations by the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer on the European Space Agency's Venus Express spacecraft indicate that the three hotspots radiate distinctly more heat than the rest of the planet. Low thermal emission is generally thought to imply a thicker lithosphere built up by surface weathering. High emissivity implies that the hot spots flows are less weathered, and therefore relatively young. The researchers further estimate the volcanic outpourings to be younger than 2.5 million years, and probably much younger -- likely 250,000 years or less -- indicating that Venus is actively reshaping its surface. A News story by R.A. Kerr in the 9 Apr issue highlighted the findings. The Multitasking Brain When it comes to task management, the prefrontal cortex is key. The anterior part of this brain region forms the goal or intention, while the posterior part serves as the brain's motivational system that drives a behavior according to the expected reward. In a study in the 16 Apr 2010 Science, Charron and Koechlin investigated how the brain negotiates performing two tasks at once (listen to the related podcast interview with Etienne Koechlin). The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging to monitor the brain activity in 32 volunteers as they performed letter-matching tasks either sequentially or concurrently (for a small monetary reward if they performed well). As expected, working on a single task at a time activated both sides of the participants' brains, setting off the anterior-to-posterior chain of command to accomplish the job. When participants took on a second task, however, the researchers observed a split in brain activity such that activity in the left side of the prefrontal cortex corresponded to one task while activity in the right side corresponded to performance of the second task. Each side of the brain worked independently, pursuing its own goal and monetary reward (see the related ScienceNOW story by G. Telis). The results suggest that the brain cannot efficiently juggle more than two tasks at once because it has only two hemispheres available for task management.  Colorful Gene Transfer Colorful Gene TransferAnimal body color is an ecologically important trait, often involved in prey-predator interactions. In aphids, body color is determined by colored compounds called carotenoids -- and the type of pigmentation influences the insects' fate: Red aphids tend to be consumed by ladybugs and green ones by parasitic wasps. Most animals get their carotenoids from food, but in the 30 Apr 2010 Science, Moran and Jarvik report the unexpected discovery that the aphid genome itself encodes multiple enzymes for producing carotenoids. Even more intriguing, phylogenetic analyses indicate that these aphid genes were acquired by an ancestral aphid in a lateral transfer event from a fungus, and have since been integrated into the aphid genome and duplicated. The team further confirmed that these carotenoid genes are indeed responsible for aphid coloration. Red aphids have a 30-kilobase genomic region, encoding a single carotenoid synthetic enzyme, that is absent from green individuals. A mutation causing an amino acid replacement in this enzyme results in loss of torulene and of red body color. An accompanying Perspective by T. Fukatsu noted that "[a]lthough such [gene] transfer events might have been relatively rare, the recent explosive accumulation of eukaryotic genome information opens a new window to look into unexplored dynamic evolutionary processes." Sinking Sea Floors The depths of ocean bottoms are slowly, but constantly fluctuating in response to the generation (at mid-ocean ridges) and consumption (at subduction zones) of sea-floor material. Because older sea floor is susceptible to sinking as it cools, it has been assumed that sea-floor depth varies directly with its age. However, scientists have found that in the oldest parts of the seafloor, which are also the parts farthest away from the mid-ocean ridges, the ocean bottom tends to be considerably shallower than expected. In the 2 Apr 2010 Science, Adam and Vidal offered a new explanation for this curious variation of sea-floor depth. The researchers reviewed measurements and topography of the seafloor at nearly 800 locations across the entire Pacific, compared those measurements with depths predicted by models, and then analyzed the results using a new hypothesis about the flow of heat within the mantle. They found that the discrepancies between the real depths of the sea bottom and the depths predicted by standard models can be accounted for by spreading out the heat from the mantle farther away from the mid-ocean ridges (see the related ScienceNOW story by P. Berardelli). Thus, convection in the mantle underlying the oceanic crust seems to play a key role in determining ocean depth. An accompanying Perspective by M. Tolstoy noted that the Pacific depth profile is simpler than those in other ocean basins, so more work will be needed to show that this same explanation is globally applicable. Diced DNA Degradation of chromosomal DNA is one of the hallmarks of programmed cell death, or apoptosis. Mammalian cells undergoing apoptosis destroy DNA with a deoxyribonuclease known as DFF40. Cells of the worm C. elegans are also subject to apoptotic DNA degradation, but do not have a DFF40 enzyme. In a study described in the 16 Apr 2010 Science (published online 11 Mar), Nakagawa et al. searched for other nucleases that might be involved in worm apoptosis and got an unexpected result. The team found that the RNA-cleaving enzyme Dicer, which is well known for its role in sequence-specific silencing of gene expression, is cleaved by a protease and converted to a DNA-cleaving enzyme that initiates the degradation of chromosomal DNA during apoptosis. Conservation of this enzymatic switch may mean that Dicer serves as an apoptotic DNase in higher organisms as well. An accompanying Perspective by Q. Liu and Z. Paroo noted the possibility that the DNA-cleaving activity of Dicer governs other aspects of chromosome dynamics. In Science Signaling

|