This month in Science Roundup: Special Issue Introduction For decades, silicon-based electronics have driven technological breakthroughs that affect virtually all aspects of everyday life. But with the growing push toward devices that are smaller and cheaper, faster and more powerful, has silicon reached its limits? A special section of the 26 Mar 2010 Science explored advances in materials research that are fueling the next generation of electronic gadgetry. A series of Review and Perspective articles examined the limits of silicon transistors and efforts to redesign them, opportunities for new electronics afforded by transition metal oxides and oxide interfaces, and developments in stretchable electronics. And a pair of News stories discussed the looming scarcities of rare-earth elements vital to the electronics industry and the promise of nitrogen-based semiconductors known as nitrides. Of related interest online, a Science Translational Medicine paper by Viventi et al. published on 24 Mar described a method of using flexible electronics to measure the patterns of a beating heart, and Science Careers profile featured a young British researcher working on nanoscale structures in gallium nitride. Fairness in Modern Society Experiments in psychology and economics have demonstrated that in industrialized societies all over the world, a substantial fraction of individuals will behave fairly in anonymous interactions and will punish others deemed to have behaved unfairly. What motivates this prosocial behavior? In a Research Article in the 19 Mar 2010 Science, Henrich et al. measured fairness in thousands of individuals from 15 diverse populations, including foraging and nomadic hunter-gatherer groups, to gain an understanding of the evolution of trustworthy exchange among human societies. Fairness was quantified using three economic games known as the Dictator, Ultimatum, and Third-Party Punishment games. The researchers found that fairness increases with the level of a society's market integration, measured as the percentage of a household’s total calories that were purchased from the market. Participation in a world religion was also associated with fairness, although not across all measures. And larger-scale societies were found to exercise punishment to a greater extent than smaller-scaled ones. These results suggest that modern prosociality is not solely the product of an innate psychology, but also reflects norms and institutions that have emerged over the course of human history. A Perspective by K. Hoff highlighted the study.  Sperm Wars Sperm WarsFor males of some species, mating is just the first step toward winning the battle to pass on their genes. Females sometimes mate more than once in quick succession, filling their reproductive tract with rival sperm that must compete for access to the unfertilized eggs. Two studies published in Science this month revealed new details about the complexity and fierceness of sperm competition in insects (see the related News story by E. Pennisi). In a study published online in ScienceExpress on 18 Mar, Manier et al. developed two fruit fly lines that produce different fluorescent proteins in the sperm head -- one green and the other red -- thus enabling the team to follow sperm activity within the female reproductive tract in real time. Female flies were allowed to mate with one male strain and then the other a few days later. The team observed that the first sperm in the reproductive tract swim to the female's sperm-storage organ, but that many are physically displaced by the second wave of sperm. Following the ejection of excess sperm by the female, the remaining competing sperm seemed to have an equal chance of fertilizing an egg. In a Report in the 19 Mar 2010 issue, den Boer et al. found that sperm in some bees and ants do more than physically displace rivals. The researchers compared species of bees and ants with queens that mate either once or multiple times and found that sperm competition has driven the evolution of compounds in the male accessory gland that protect a male's own sperm while damaging another male's sperm. To counteract the male effect, queens produce compounds that mitigate sperm destruction and maximize the number of her offspring. Platinum-Free Diesel The efficiency advantages inherent in diesel-based combustion engines are counterbalanced by the production of smog-forming nitrogen oxides. Removing these pollutants currently requires expensive precious metals like platinum. Now, in a Report in the 26 Mar 2010 Science, Kim et al. describe an inexpensive catalyst that shows promise for mitigating pollutants from diesel exhaust without the use of precious metals. The team showed that at a diesel engine's cruising temperature, a catalyst consisting of a mixture of palladium and perovskite oxide containing lanthanum, strontium, and manganese can remove pollutants at least as well as a traditional platinum catalyst -- though is slightly less effective when the engine is cold (see the related ScienceNOW story by T. Wogan). An accompanying Perspective by J. E. Parks II noted that the new technology , which uses cheaper and more abundant elements, will allow engineers greater flexibility as they work to develop better catalysts in a market where volatile platinum prices have made commercial introduction of fuel-efficient, diesel-driven vehicles challenging.  Matching Flu Viruses Matching Flu VirusesAt least one feature of the "novel" H1N1 influenza virus that caused a human pandemic last year is not so novel. Two separate groups reporting in Science and Science Translational Medicine this month showed that the virus' surface protein, hemagglutinin (HA) -- which spikes cells and starts an infection -- closely matches the HA in the H1N1 virus responsible for the 1918 pandemic (see the News story by J. Cohen in the 26 Mar issue). In a Report published online ahead-of-print in ScienceExpress, Xu et al. crystallized HA from both the 1918 and 2009 pandemic viruses and showed that their structures are very similar and that the few amino acid differences between the strains are mainly confined to one small region. Moreover, these HA structures are distinct from seasonal influenza strains that have circulated in the intervening decades. The structural similarity provides an explanation for why the 2009 pandemic largely spared the elderly (listen to the related podcast interview with senior author Ian Wilson). In the 24 March issue of Sci. Transl. Med., Wei et al. showed that vaccination of mice with the 1918 strain protected against subsequent lethal infection by 2009 virus, and vice versa, because the antibodies raised are directed against HA regions that are so similar. The antibodies that neutralize the pandemic strains are ineffective against seasonal flu, however. That is because the HA of seasonal flu strains has two sites, not present in the pandemic HA, to which sugar groups are added, shielding seasonal flu HA from inhibition by the antibodies that act against the pandemic strains. These findings will help inform future vaccine design. Sestrins and Aging The protein kinase TOR (target of rapamycin) is an important regulator of cell growth and metabolism, stimulating growth by increasing protein and lipid synthesis while inhibiting the catabolic breakdown of cells. Persistent activation of TOR causes an imbalance between anabolic and catabolic processes and is associated with diverse age-related disorders. Conversely, inhibition of TOR prolongs life span and increases quality of life by reducing the incidence of age-related pathologies. In a Research Article in the 5 Mar 2010 Science, Lee et al. reported that sestrins -- highly conserved proteins that accumulate in cells exposed to stress -- prevent excessive TOR activation and delay the onset of age-related pathologies through a negative-feedback mechanism. The team found that loss of sestrin in fruit flies caused the accumulation of damaging reactive oxygen species and development of age-associated problems including fat accumulation, muscle degeneration, and heart abnormalities similar to those that plague aging humans with a sedentary lifestyle. In an accompanying Perspective, Topisirovic and Sonenberg note that drugs that mimic the molecular effects of sestrin could open new therapeutic avenues to target age-related pathologies.  Arctic Methane Venting Arctic Methane VentingWetlands and permafrost soils, including the sub-sea permafrost under the Arctic Ocean, contain at least twice the amount of carbon that is currently in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. There is concern that climate warming could warm waters enough to release a sizable fraction of this carbon as carbon dioxide and/or methane into the atmosphere, leading to even more warming. Now, in the 5 Mar 2010 Science, Shakhova et al. report results from repeated ocean surveys between 2003 and 2008, which show that that more than 80% of the bottom water, and more than 50% of the surface water over the East Siberian Arctic Shelf is supersaturated with methane that is being released from sub-sea permafrost. Moreover, the flux of methane into the atmosphere is on par with previous estimate of methane venting from the entire world ocean. This unexpected outgassing could impact Arctic climate in important ways (listen to the related podcast interview with lead author Natalia Shakhova). An accompanying Perspective by M. Heimann discussed the importance of both on-the-ground monitoring and remote-sensing technologies for understanding and predicting changes in the natural methane cycle over the coming decades. Thalidomide Teratogenicity Target Prescribed as an antinausea drug for pregnant women in the late 1950s and early 1960s, thalidomide caused severe birth defects in as many as 10,000 children before its use was discontinued. Today, thalidomide is used under strict control for the treatment of multiple myeloma and complications of leprosy, but little has been known about how it causes limb malformations and other developmental defects. In a Research Article in the 12 Mar 2010 Science, Ito et al. showed that the protein cereblon is a primary target of thalidomide, using zebrafish and chicken as animals models. Their experimental results suggest that thalidomide exerts its teratogenic effects (fetal malformations), at least in part, by binding to cereblon and inhibiting associated enzymatic activity important for limb development (see the related ScienceNOW story by G. Vogel). Although cereblon is widely expressed in embryonic and adult tissues, thalidomide has specific effects on limbs, ears, eyes, gut, and kidneys. The researchers thus suggest that cereblon is necessary, but not sufficient for thalidomide teratogenicity and that downstream components are likely to contribute to the drug's tissue-specific effects. Further understanding of thalidomide's mechanism of action may help scientists develop less-toxic versions of the drug.  Inside Titan Inside TitanThe interior structure and composition of solar system bodies are key to understanding their origin and evolution. In the 12 Mar 2010 Science, Iess et al. used gravity data from four flybys of the Cassini spacecraft past Saturn's largest moon Titan to model the moon's gravity field and probe its deep interior structure. The data indicate that Titan has a partially differentiated internal structure, which could be explained by either incomplete separation of the primordial mixture of rock ice from which Titan formed, or the presence of a core in which a large amount of water remains chemically bound in silicates. Both interpretations differ from previous interior models with strong implications for Titan's thermal history. As noted in an accompanying Perspective by F. Sohl "[t]he implication is that Titan's interior may have failed to get sufficiently hot for melting of a substantial portion of the primordial ice-rock mixture to occur and separation of ice from rock to proceed." Taming Turbulence From domestic water pipes to oil and natural gas conduits, pipes feature prominently in the infrastructure of everyday life. Even at moderate velocities, pipe flows are sensitive to minute disturbances caused by roughness in the pipe or other irregularities, which can lead local eddies to grow into full-scale disruption of otherwise smooth, or laminar, flow. Such turbulence can dramatically increase the power required to pump a fluid at the same rate and can also lead to structural vibrations and the damaging of equipment. Now, in a Report in the 19 Mar 2010 Science, Hof et al. show that injecting a fluid jet into a pipe at an optimized location eliminates the growth of upstream disturbances and can prevent the overall flow from becoming turbulent. Importantly, the energy cost for implementing this strategy is less than the benefit gained by maintaining a laminar flow -- an essential element of practical flow control. An accompanying Perspective by B.J. McKeon noted that in addition to the obvious economic impact and energy implications of implementing this strategy, the approach "could give insight into fundamental physics of fully developed turbulence, which provides an equally challenging problem to fluid mechanicians."

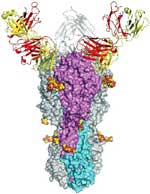

|